Asking better questions of progress

Reflecting (ranting) on the world's desire to be like us

“The industrial Paradise is a fantasy in the minds of the privileged and the powerful; the reality is a shambles.” — Wendell Berry

1I recently went to Johannesburg, South Africa, to participate in the wedding of an old friend, roommate, and brother. It was an incredible trip—my first time across the ocean—full of experiences and relationships I never knew to expect that culminated in a beautiful wedding. On my final day in South Africa, I found myself wandering through a bookstore looking for something for the ride home that would continue to enlarge my perspective.

My ongoing interest in agrarianism and agriculture led me to A Country of Two Agricultures: The Disparities, the Challenges, the Solutions by Wandile Sihlobo, published just a few months ago in 2023. It was full of new (to me) information forcing me to skim Wikipedia pages once I left the plane. At the end of it, though, I found myself thinking more about the United States than South Africa. I had new questions for myself.

By all accounts, Sihlobo is an expert in his field as an agricultural economist, a member of various important-sounding councils I know little about, and a Senior Lecturer Extraordinary at Stellenbosch University. It should go without saying I am not qualified to critique the nuances of the policy, attitude, and governmental shifts Sihlobo calls for in his book, but I do feel equipped to ponder the significance of a country that seems destined to follow the path of industrialization in the footsteps of countries like my own.

South African agriculture is dichotomized into mostly white-owned commercial farms and mostly black-owned subsistence farms as a result of past regimes and atrocities that have only been marginally corrected in the modern country’s purportedly democratic government (it’s not my place to comment on the specifics as an ignorant outsider, but this seems to be the general view). There are exceptions, such as the black commercial farmer Gift Mafuleka highlighted by Sihlobo, but the dichotomy is real.

For Sihlobo, part of the solution is a “better fewer, but better” approach focused on helping the industrialization of the black farmers that can do so rather than spreading support too thin over the many small, more subsistence-based farmers, and opportunistically seeking improved export markets in response to modern global economic shifts. He seeks an industrialization of agriculture into “agribusiness” that will provide an economic boon to South Africa and improve the stability of the nation-state and its inhabitants.

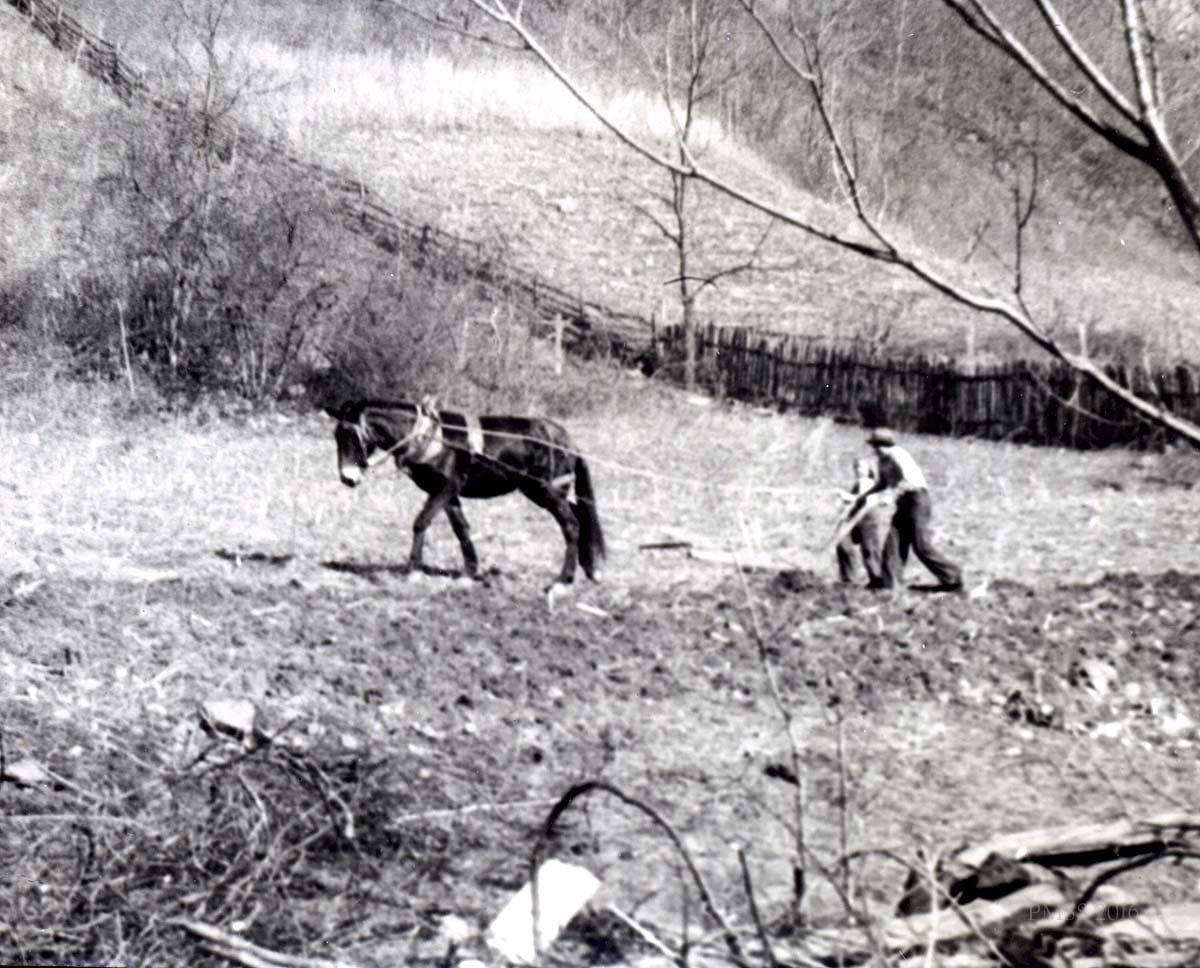

I’m sure Sihlobo is generally right about the cause-and-effect of the progress he seeks. And I’m sure it works, because I was born into a world several decades “ahead” of South Africa in terms of agribusiness and I reap the benefits. But I am also aware of the withered rural culture in America that it engendered and the incredible damage to the land, offset—only in terms of production—by industrial tools including heavy machinery, pesticides, and fertilizers whose most damaging effects are primarily felt by people I will never meet.

2It isn't my place to tell someone halfway around the globe how to seek improved welfare, but I can ask myself what kind of progress I want. The “better fewer, but better” approach is merely a nice way of saying “get big or get out,” one of the most damaging events to ever happen to American culture and agriculture. What if the solution is to embody cultural and agricultural values that more closely emulate the indigenous subsistence farmers of South Africa or the American farmers like Wendell Berry who put the health of the community and the land over the health of their wallets or the economy at large?

South African policymakers should have a ‘commercialisation approach’ in mind when thinking about distributing land and introducing broader agricultural development programmes. Similarly, traditional leaders should aspire to have commercial farming in their regions to improve economic activity and help create employment (large-scale horticulture creates sustainable jobs)…South Africa’s current dualistic farming structure is not sustainable.3

Sihlobo talks a lot about “sustainability” in his book, but agricultural and ecological sustainability are not part of his intended semantic range. He is concerned first and foremost with economic sustainability, which benefits primarily the nation-state. To my fellow Americans and other privileged parties I must ask, “of what value is the nation-state?” We have turned food into a weapon that fuels our fat-and-happy lifestyle and can be used as a carrot on a stick in our negotiations with other countries, but what has it cost us and our global neighbors?

The exploitive always involves the abuse or the perversion of nurture and ultimately its destruction. Thus, we saw how far the exploitive revolution had penetrated the official character when our recent secretary of agriculture remarked that ‘Food is a weapon.’…Food is not a weapon. To use it as such—to foster a mentality willing to use it as such—is to prepare, in the human character and community, the destruction of the sources of food. The first casualties of the exploitive revolution are character and community. When those fundamental integrities are devalued and broken, then perhaps it is inevitable that food will be looked upon as a weapon, just as it is inevitable that the earth will be looked upon as fuel and people as numbers or machines. But character and community—that is, culture in the broadest, richest sense—constitute, just as much as nature, the source of food.” — Wendell Berry

4I cannot blame another country for desiring the stability, wealth, or agri-weapons had by the States; I cannot tell Sihlobo or any other South African what to do with their land and country. I can, however, seek powerful counterpoints in my own context that call Americans into increased awareness and warn other countries of following in our footsteps. I can point to communities close to home like the Amish and Mennonites who, as ecclesial bodies, attempt to answer questions that most Christians are too ignorant or lazy to ask, and suggest they provide an example of prophetic Christianity we should learn from. I can ask: what kinds of wealth are important? what kinds of wealth should we sacrifice for the sake of living lives that improve the land we live on and reduce damage to land far away?

“If change is to come, then, it will have to come from the outside. It will have to come from the margins. As an orthodoxy loses its standards, becomes unable to measure itself by what it ought to be, it comes to be measured by what it is not. The margins begin to close in on it, to break down the confidence that supports it, to set up standards clarified by a broadened sense of purpose and necessity, and to demonstrate better possibilities…this sort of change is a dominant theme of our tradition, whose “central” figures have often worked their way inward from the margins. It was the desert, not the temple, that gave us the prophets;” — Wendell Berry

5Living a godly life means pursuing the margins for what they offer that the orthodoxy of cities, universities, governments, and institutions cannot. Reducing poverty is a worthy aim—but I’m afraid that we’ve attached false value to the lives of the wealthy. I’m afraid that reducing poverty by helping the poor become exploiters like the rest of us will only strip the world of real nurturing value.

Something similar happened in America with the women’s empowerment movements. By no means is it an unworthy goal to pursue a world where men and women are equally able to live autonomous lives, but we created problems by devaluing what women traditionally did and overvaluing what men did in the new industrialized economy. We do the same thing with agriculture.

“Women traditionally have performed the most confining—though not necessarily the least dignified—tasks of nurture: housekeeping, the care of young children, food preparation. In the urban-industrial situation the confinement of these traditional tasks divided women more and more from the ‘important’ activities of the new economy. Furthermore, in this situation the traditional nurturing role of men—that of provisioning the household, which in an agricultural society had become as constant and as complex as the women’s role—became completely abstract; the man’s duty to the household came to be simply to provide money. The only remaining task of provisioning— purchasing food—was turned over to women. This determination that nurturing should become exclusively a concern of women served to signify to both sexes that neither nurture nor womanhood was very important.” — Wendell Berry

6In America, the nurturing potential of agriculture and silviculture (what foresters like myself try to practice) is almost unrecognized. What matters are revenue streams and products that keep Americans consuming and other countries reliant.

Maybe we, as individual or ecclesial bodies, can pursue the margins and learn from them. Maybe we can help the poor the most by emulating their nurturing qualities and ceasing to exploit them. Maybe blind industrialization and “better fewer, but better” is part of the problem. Maybe the American ideal of one farmer feeding an average of 100-160 people is too extreme.

If South Africa goes the way of America, there is good reason to fear for the fate of the country’s many beautiful cultures and languages—at least for now.

In just a little while, the wicked will be no more;

though you look carefully at his place, he will not be there.

But the meek shall inherit the land

and delight themselves in abundant peace. — Psalm 37

But what do I know? I’m just an American living a fat-and-happy lifestyle thanks to agricultural policies that built a modern nation-state on exported poverty and the backs of others.7

“To bring under the sway of Christianity…there is only one means. That means is the propagation among these nations of the Christian ideal of society, which can only be realized by a Christian life, Christian actions, and Christian examples…Instead of that we begin by establishing among them new markets for our commerce, with the sole aim of our own profit; then we appropriate their lands, i.e. rob them; then we sell them spirits, tobacco, and opium, i.e. corrupt them; then we establish our morals among them, teach them the use of violence and new methods of destruction, i.e., we teach them nothing but the animal law of strife, below which man cannot sink, and we do all we can to conceal from them all that is Christian in us. After this we send some dozens of missionaries prating to them of the hypocritical absurdities of the Church, and then quote the failure of our efforts to turn the heathen to Christianity as an incontrovertible proof of the impossibility of applying the truths of Christianity in practical life.” — Leo Tolstoy

Opening quote from The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture by Wendell Berry.

Hadden Turner at Over the Field deals with some of these same ideas. I recommend checking out his substack.

Wandile Sihlobo, A Country of Two Agricultures: The Distarities, the Challenges, the Solutions. Tracey McDonald Publshers, 2023.

Quote from The Unsettling of America.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Final quote from Leo Tolstoy’s 1894 book The Kingdom of God is Within You, translated by Constance Garnett. One of the peoples Tolstoy had in mind in this excerpt was the Zulu nation, who would go on to be treated exactly how he described here and are now mostly living in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa, one of the poorer, largely subsistence-based regions Sihlobo focuses on in his book.

This is excellent, Wayne. I inwardly shouted yes when I read this:

"Reducing poverty is a worthy aim—but I’m afraid that we’ve attached false value to the lives of the wealthy. I’m afraid that reducing poverty by helping the poor become exploiters like the rest of us will only strip the world of real nurturing value."

So much "development" is premised on moving the poor to the mass consumer society in Rostow's stages of growth model. This neglects to account for how environmentally (and community) unsustainable this lifestyle is - and the myriad new problems such a society will face. Sadly, It seems we never learn.

I have not read Sihlobo's book but, as a South African, I am painfully aware of the divide about which it speaks. I agree that it is unsustainable, but don't believe the industrialisation model will serve us well. Like you, I worry about the damage to land and rivers, the elimination of small-scale farmers from the market, and exploitation by powerful countries who are only interested in profit.

An excellent post. Thank you.