The kenotic Creator

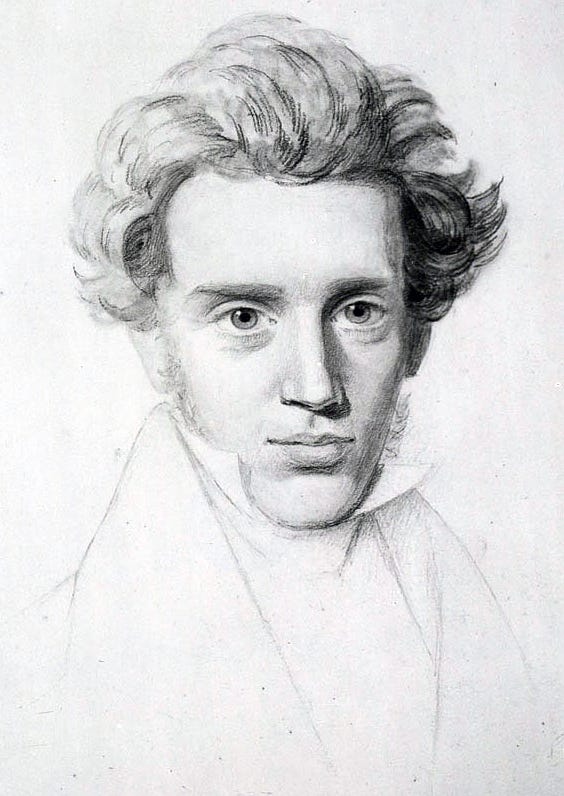

Some thoughts about the God of self-denial with a little help from Søren Kierkegaard

If you’re like me, there’s a decent chance you’ve never heard this word before, which didn’t even exist until the 1800s. However, it wasn’t a new idea when the word was invented—just an attempt at a more exact definition. So what’s it all about, anyway?

The concept dates back at least to the New Testament. When Jesus, fully God, came to earth to experience an entire life as fully human,1 He performed an act of self-denial, renouncing at least for a time some of His divine attributes or privileges. The word “kenosis” was created from the Koine Greek of the New Testament to capture the idea of this renunciation:

Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility count others more significant than yourselves. Let each of you look not only to his own interests, but also to the interests of others. Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied [ekenōsin] himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.2

Jesus, in His self-emptying, provided the ultimate example of humility and putting the interests of others first. There are many aspects to this emptying, or “kenosis”: Jesus’ birth in a place for animals to a poor family following a socially conspicuous pregnancy, His foregoing of omniscience (forcing Him to rely fully on the Father and Spirit for superhuman knowledge),3 His constant self-sacrifice in putting His physical needs behind those of people who sought Him for help, His patience with both His followers and His enemies, and, of course, His willing death on the cross, where He poured Himself out as a sacrifice for all—friend and foe alike.

But are God’s kenotic acts limited to the short decades Jesus spent walking the earth as a human? If we allow ourselves a broad understanding of kenosis, it immediately becomes clear that God is no stranger to scandalous acts of putting others first, especially when they don't deserve it.

There are two particular kenotic acts that strike me personally, and I think they are important for not only our understanding of God but also the way we treat our neighbors. We'll start with God's kenotic affirmation of free will in His created beings. I think it will become clear why some consider this a “self-emptying.”

These are the clans of the sons of Noah, according to their genealogies, in their nations, and from these the nations spread abroad on the earth after the flood. Now the whole earth had one language and the same words. And as people migrated from the east, they found a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there. And they said to one another, “Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.” And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar. Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be dispersed over the face of the whole earth.” And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of man had built. And the LORD said, “Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language, and this is only the beginning of what they will do. And nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and there confuse their language, so that they may not understand one another’s speech.” So the LORD dispersed them from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. Therefore its name was called Babel, because there the LORD confused the language of all the earth. And from there the LORD dispersed them over the face of all the earth.4

The Lord “dispersed” the people He created and saved them from destruction they deserved; instead of destroying the people who had wholly rejected God for the third time, He let them go. Moses, during his song in Deuteronomy, recalled and described the event with an interesting perspective:

Remember the days of old;consider the years of many generations;ask your father, and he will show you,your elders, and they will tell you.When the Most High gave to the nations their inheritance,when he divided mankind,he fixed the borders of the peoplesaccording to the number of the sons of God.But the LORD’s portion is his people,Jacob his allotted heritage.

5Instead of destruction, God handed His people over to beings and rulers they preferred. Paul describes the same event in Romans, or at least has something like the “Deuteronomy 32 worldview”6 in his head as he writes:

For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who by their unrighteousness suppress the truth. For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse. For although they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things.

Therefore God gave them up in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, to the dishonoring of their bodies among themselves, because they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed forever! Amen.

For this reason God gave them up to dishonorable passions...since they did not see fit to acknowledge God, God gave them up.7

“God gave them up.” When God's children decided worshipping Yahweh was not necessary to reach the heavens, the domain of the gods, He “gave them up” and let them be led by false gods they preferred. When His children jumped the gun and dismissed God's plans and timing, He gave them “their inheritance” early—like the prodigal son.8 Of course, He would raise up another “firstborn son”9 in His continual attempt to find people who would freely choose to receive His blessings, but He never denies His children freedom. This is perhaps the first of God's kenotic acts: we, who have no rights or justifications before our Creator, are granted freedom even to reject reality and the God whose “invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world.” In offering this freedom, God empties Himself.

Many readers of the Bible have recognized the scandalous nature of the Christian God's approach to His subjects; Søren Kierkegaard is one of my favorite thinkers who saw a kenotic God in Scripture.10 In one of his journals, he asserted a form of kenoticism as the reason an all-powerful God allowed evil to occur in His created world:

The whole question of the relation of God's omnipotence and goodness to evil…is resolved quite simply in the following way. The greatest good, after all, that can be done for a being, greater than anything else that one can do for it, is to make it free. In order to do just that, omnipotence is required. This seems strange, since it is precisely omnipotence that would supposedly make dependent. But if one will reflect on omnipotence, one will see that it also must contain the unique qualification of being able to withdraw itself again in a manifestation of omnipotence in such a way that precisely for this reason that which has been originated through omnipotence can be independent.11

In other words, only an all-powerful being could give itself away entirely to create something truly free and able to reject its creator. And since God is good and desires a family that can choose to love Him out of their own free will, it is inevitable God empties Himself (allows mutual withdrawal at our behest) in a way that allows us to commit acts wholly other than His own character and wholly other than the character of a creation bearing His image—acts of evil. Like grace, we are offered this freedom without earning it. Kierkegaard continues:

This is why one human being cannot make another person wholly free, because the one who has power is himself captive in having it and therefore continually has a wrong relationship to the one whom he wants to make free...Only omnipotence can withdraw itself at the same time it gives itself away, and this relationship is the very independence of the receiver. God's omnipotence is therefore his goodness. For goodness is to give away completely, but in such a way that by omnipotently taking oneself back one makes the recipient independent. All finite power makes dependent; only omnipotence can make independent, can form from nothing something that has continuity in itself through the continuous withdrawing of omnipotence.12

One of the best succinct formulations of the kenotic nature of God's affirmation of our free will comes from a contemporary scholar, Simon D. Podmore, who explores Kierkegaard’s idea:

The freedom of the self is an inviolable principle of possibility to which, in a profound and scandalous sense, even God submits. God surrenders to the self’s freedom out of a kenotic freedom: a divine freedom which sacrifices itself in the name of human freedom. This upholding of the freedom of the self—including the freedom to refuse God, to choose the unfreedom of despair—is nonetheless a source of ineffable divine sorrow. It is a wound of a sacred Love which gives itself in the only manner it can, without overpowering the freedom of the beloved. God does not, perhaps even cannot, remove from creation the possibility of saying “no” to God, even though the sustenance of this possibility constitutes an “unfathomable grief” of divine love. In this horizon of possibility, in which freedom is free even to the point of negating itself, there emerges what Kierkegaard discerns as a struggle between faith and that which faith names as “despair”. This same despair is, nonetheless, named by itself as an expression of ultimate human autonomy.13

I don't think we can truly wrap our minds around the pain God must feel when He watches us deny Him, but it's only fitting that the God of the Bible is the God of self-denial. In Podmore’s view, kenosis, freedom, and grace are connected as he concludes:

[F]reedom is also manifest in the possibility to negate “God”—a possibility of despairing negation which, out of wounded love and with “unfathomable grief”, God does not negate. As such, the kenosis of the human self…is a free response to grace: the primal kenosis of divine omnipotence, sacrificed to the inviolable divine gift of human freedom.14

Now, this isn't just an abstract discussion. It should affect the way we live our lives if we desire to follow God and bear His image.15 I'd go so far as to say it should inform how we approach the sociopolitical sphere—do we really have the right to restrict the freedoms of our neighbors and fellow children of God when even God Himself refuses to do so?16 In bearing God’s image and being Jesus’ disciple, should we not empty ourselves for others?17

But God does more than simply make us free.

When I consider your heavens,the work of your fingers,the moon and the stars,which you have set in place,what is mankind that you are mindful of them,human beings that you care for them?You have made them a little lower than the angelsand crowned them with glory and honor.You made them rulers over the works of your hands;you put everything under their feet:all flocks and herds,and the animals of the wild,the birds in the sky,and the fish in the sea,all that swim the paths of the seas.

Who are we that God is mindful of us? And yet He offers us the opportunity to share in His role as caretaker of creation.

We who have no rights before God, worthy only of the consequences of our own acts of evil or perhaps to be slaves of God,18 are offered a privileged status. This is another kenotic act.

The author of Hebrews applies the psalm to Jesus in His kenotic human form, for a short time made “lower than the angels,” and then reminds the reader that we humans will receive glory we do not deserve. Jesus, in His life and death and victory, elevates us from slavery to sonship, from a self-inflicted orphanhood to an adopted status—from dust to a resurrected form that can somehow be called brother or sister of Christ:

It is not to angels that he has subjected the world to come, about which we are speaking. But there is a place where someone has testified:

“What is mankind that you are mindful of them,a son of man that you care for him?You made them a little a lower than the angels;you crowned them with glory and honorand put everything under their feet.”In putting everything under them, God left nothing that is not subject to them. Yet at present we do not see everything subject to them. But we do see Jesus, who was made lower than the angels for a little while, now crowned with glory and honor because he suffered death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone.

In bringing many sons and daughters to glory, it was fitting that God, for whom and through whom everything exists, should make the pioneer of their salvation perfect through what he suffered. Both the one who makes people holy and those who are made holy are of the same family. So Jesus is not ashamed to call them brothers and sisters. He says,

“I will declare your name to my brothers and sisters;in the assembly I will sing your praises.”And again,

“I will put my trust in him.”And again he says,

“Here am I, and the children God has given me.”Since the children have flesh and blood, he too shared in their humanity so that by his death he might break the power of him who holds the power of death—that is, the devil—and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death. For surely it is not angels he helps, but Abraham’s descendants. For this reason he had to be made like them, fully human in every way, in order that he might become a merciful and faithful high priest in service to God, and that he might make atonement for the sins of the people. Because he himself suffered when he was tempted, he is able to help those who are being tempted.

Therefore, holy brothers and sisters, who share in the heavenly calling, fix your thoughts on Jesus, whom we acknowledge as our apostle and high priest.19

The author of Hebrews recognized that God's kenotic act of becoming human for us was connected to God's kenotic act of lifting humans up to share in His reign.

We are offered the chance to be united with Christ and share not only in His death and burial, but also in His resurrection and victory.20 We have been set free from this world in a way no human power can, which culminates in our adoption and receiving an inheritance we once rejected:

For those who are led by the Spirit of God are the children of God. The Spirit you received does not make you slaves, so that you live in fear again; rather, the Spirit you received brought about your adoption to sonship. And by him we cry, “Abba, Father.” The Spirit himself testifies with our spirit that we are God’s children. Now if we are children, then we are heirs—heirs of God and co-heirs with Christ, if indeed we share in his sufferings in order that we may also share in his glory. I consider that our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us.21

Our liberation from the bondage of sin we were born into through Adam and then earned for ourselves22 is more than just an escape from slavery. It's a shocking elevation of our status! I argue that God's lifting up of us who are ontologically inferior to be in some way sharers of Christ’s reign23 over creation—a creation healed and set free from bondage—is an act of kenosis, an emptying of His innate role to spread and share it with us. It’s so incomprehensible from a human perspective it almost feels heretical to write this!

I think we worship the God of self-denial, and I think He doesn’t ask anything of us He hasn’t already done for us. What do you think?

The concept of Jesus as having been on Earth as fully God and fully human is sometimes referred to as the hypostatic union. There may be ways of formulating the idea of kenosis in a way that denies the hypostatic union or some other aspect of God’s full divinity, which makes some people afraid of the concept altogether. I affirm the hypostatic union and Jesus’ full divinity, but will make no other mention of what some call the kenotic heresy; I am not concerned by it.

Php 2:3-8. Biblical quotations will be from the ESV unless otherwise noted.

The idea that Jesus denied Himself certain divine attributes like omniscience during His decades as a human is offensive or heretical to some; I refer you to footnote #1.

Gen 10:32-11:9.

Deut 32:7-9.

Rom 1:18-28.

Luke 15:11-32.

Exod 4:22.

For an introduction to the topic, especially as it regards the hypostatic union, see Kierkegaard’s Kenotic Christology by David R. Law, published in 2013 by Oxford University Press.

Søren Kierkegaard, Journals and Papers, 7 volumes, ed. and trans. By Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Bloomington, Indiana: Bloomington University Press, 1967-1978), volume 2, entry 1251.

Ibid.

Podmore, S.D. 2017. The Anarchē of Spirit: Proudhon’s Anti-theism and Kierkegaard’s Self in Apophatic Perspective. In: Christoyannopaulos, A. and Adams, M. S. (eds.) Essays in Anarchism and Religion: Volume I. Pp 238-282. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press.

Ibid.

Julie Tomlin Arram puts it this way: “what is required of us if we are to demonstrate a faith that is inspired by a self-emptying God?” (Discovering Kenarchy: Contemporary Resources for the Politics of Love, 2014)

Of course, God retains the right to judge and to stop offering second chances. Paul addresses this in Rom 3:4-8, and the Old Testament desribes several instances where God seems to “lock in” the choices of people who reject Him (e.g. Exod 7:3, Deut 2:30). In perhaps a similar way, we must affirm the freedom God gives to all people without neglecting special needs of the poor and marginalized.

cf. 2 Tim 4:6.

e.g. Col 1:7, 2 Tim 2:24, 2 Pet 1:1, 2:16, Jude 1:1.

Heb 2:5-18, NIV.

Rom 6.

Rom 8:14-18, NIV.

e.g. Rom 3:23, 5:12, 6:23.

e.g. 2 Tim 2:12, Rev 20:6.