Redux: The kenotic Creator

Revisiting Kierkegaard's understanding of an all-powerful God and contrasting it with Bakunin's in "God and the State"

“it is objected that the ultimate loss of a single soul means the defeat of omnipotence. And so it does. In creating beings with free will, omnipotence from the outset submits to the possibility of such defeat. What you call defeat, I call miracle; for to make things which are not Itself, and thus to become, in a sense, capable of being resisted by its own handiwork, is the most astonishing and unimaginable of all the feats we attribute to the Deity.” — C.S. Lewis

The kenotic Creator

Check out this previous post about the God of self-denial for a more in-depth look at God's kenotic acts

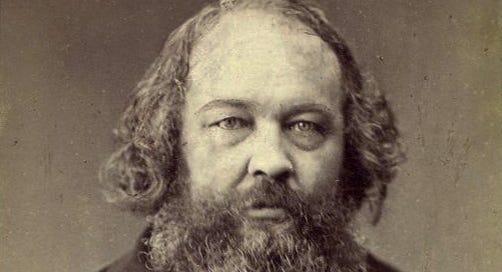

1I recently read God and the State,2 an incomplete work published posthumously in 1882 by the radical anarchist and atheist Mikhail Bakunin, and heard an echo of one of Bakunin’s contemporaries, Søren Kierkegaard. Both men held freedom in high regard and recognized that someone who holds power over another cannot truly make the other free, and both men applied that logic, to some extent, to the Christian God. In the words of Bakunin,

For, if God is, he is necessarily the eternal, supreme, absolute master, and, if such a master exists, man is a slave; now, if he is a slave, neither justice, nor equality, nor fraternity, nor prosperity are possible for him. In vain, flying in the face of good sense and all the teachings of history, do they [Christians] represent their God as animated by the tenderest love of human liberty: a master, whoever he may be and however liberal he may desire to show himself, remains none the less always a master. His existence necessarily implies the slavery of all that is beneath him. Therefore, if God existed, only in one way could he serve human liberty—by ceasing to exist.

Now, I don’t think Bakunin’s logic was entirely wrong even though I disagree with his presuppositions and conclusion: namely, that the God of the Bible doesn’t exist, and if He did, He wouldn’t be the God of love He claims to be.3 Bakunin did recognize something central to the whole notion of having power over another being—after all, he was an anarchist. However, his understanding of the depth of love in the Christian God was lacking.

I’d like to revisit our citation from Kierkegaard’s journals in which he considered the reality of evil’s existence in a world created by a supposedly loving and all-powerful God. Kierkegaard agrees that someone who holds power over another can never make them free—or does he?

Bakunin perceived the concept of omnipotence as on a continuum with the kind of power and authority humans have. Being all-powerful is just having power to the max, right? No wonder he couldn’t conceive of a loving all-powerful God, surrounded as he was by fine examples of human oppressors.

Kierkegaard saw it differently. Omnipotence isn’t in the same plane as human power—it’s a different kind altogether:4

The whole question of the relation of God's omnipotence and goodness to evil…is resolved quite simply in the following way. The greatest good, after all, that can be done for a being, greater than anything else that one can do for it, is to make it free. In order to do just that, omnipotence is required. This seems strange, since it is precisely omnipotence that would supposedly make dependent. But if one will reflect on omnipotence, one will see that it also must contain the unique qualification of being able to withdraw itself again in a manifestation of omnipotence in such a way that precisely for this reason that which has been originated through omnipotence can be independent.5

It “seems strange,” says Kierkegaard, because if you look at power linearly like Bakunin you’re left accepting Bakunin’s conclusions: either there is no God or we are not free and should rebel like the great emancipator, Satan. Kierkegaard continues:

This is why one human being cannot make another person wholly free, because the one who has power is himself captive in having it and therefore continually has a wrong relationship to the one whom he wants to make free...Only omnipotence can withdraw itself at the same time it gives itself away, and this relationship is the very independence of the receiver. God's omnipotence is therefore his goodness. For goodness is to give away completely, but in such a way that by omnipotently taking oneself back one makes the recipient independent. All finite power makes dependent; only omnipotence can make independent, can form from nothing something that has continuity in itself through the continuous withdrawing of omnipotence.6

God could do something with His infinite power that humans could not do for each other: He could empty Himself into us as a creative act and equally withdraw Himself to make us free. It’s a shocking move by God that has dumbfounded us for millennia, which Kierkegaard observes, “The fact that God could create free beings vis-à-vis of himself is the cross which philosophy could not carry, but remained hanging from.”7 Bakunin made no such distinction between the “finite power” that makes one dependent and the “omnipotence” that can make one independent. Instead of being made free by an omnipotent being, Bakunin saw freedom as something we earn for ourselves, saying, “the spontaneous action of the people themselves alone can create liberty.” Bakunin probably would have been willing to apply this statement of his to God, if Bakunin had believed Him to exist:

It is the characteristic of privilege and of every privileged position to kill the mind and heart of men. The privileged man, whether politically or economically, is a man depraved in mind and heart.

It is unfortunate Bakunin was left full of anger and unaware of the true God. Bakunin and his ilk are left unfulfilled, ever striving to shed more of the beast within in an eternal struggle left to posterity, as he recognizes:

the Christian Christ, already completed in an eternal past, presents himself as a perfect being, while the completion and perfection of our Christ, science, are ever in the future…Our Christ, then, will remain eternally unfinished[.]

How did Bakunin get it so wrong? The apostle Paul, an intelligent man in his own right, recognized that the intelligent and independent people of this world will have the hardest time with the message of the real Christ:

For the word of the cross is folly to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. For it is written,

“I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning I will thwart.”Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? For since, in the wisdom of God, the world did not know God through wisdom, it pleased God through the folly of what we preach to save those who believe. For Jews demand signs and Greeks seek wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles, but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. For the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men. (1 Cor 1:18-25, ESV)

Bakunin thought it “very fortunate for Christianity that it met a world of slaves” for the message of the cross sounded like salvation in the ears of the oppressed. He was right.

Bakunin embodies the spirit of Paul’s ancient warning perfectly:

The doctrine taught by the apostles of Christ, wholly consoling as it may have seemed to the unfortunate, was too revolting, too absurd from the standpoint of human reason, ever to have been accepted by enlightened men…with what joy the apostle Paul speaks of the scandale de la foi; and of the triumph of that divine folie; rejected by the powerful and wise of the century, but all the more passionately accepted by the simple, the ignorant, and the weak-minded!

If being an enlightened man means failing to know the love of Christ, I'd rather be simple and ignorant!

One reason Bakunin was so wrong about the God of the Bible is he saw many people profess that name while continuing to participate in the oppressive regimes of the secular world. Was he entirely wrong when he said, “In history the name of God is the terrible club with which all divinely inspired men, the great ‘virtuous geniuses,’ have beaten down the liberty, dignity, reason, and prosperity of man”?

Opening quotation from The Problem of Pain, 1940.

All quotes from God and the State will be from Benjamin R. Tucker’s translation (1916).

The absurdist philosopher Albert Camus put it this way: “For in the presence of God there is less a problem of freedom than a problem of evil…either we are not free and God the all-powerful is responsible for evil. Or we are free and responsible but God is not all-powerful” (The Myth of Sisyphus, 1955, translated by Justin O’Brien). In the case of both Bakunin and Camus, the logic is sound only if God is unable to make someone free while retaining omnipotence.

I doubt this is the way Kierkegaard would have described it, but this is my take.

Søren Kierkegaard, Journals and Papers, 7 volumes, ed. and trans. By Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Bloomington, Indiana: Bloomington University Press, 1967-1978), volume 2, entry 1251.

Ibid.

Søren Kierkegaard. 1835. Journals. In: A Kierkegaard Anthology, edited by Robert Bretall. Pg 10. Princeton University Press, 1973.