Learning from our spiritual heritage: Roger Williams

What can an eccentric exile in 1600s Massachusetts teach us about radical love?

Throughout the long arc of history, God has always preserved a remnant of a people committed to serving Him faithfully, people willing to risk everything and everyone to do so. Often, they were persecuted by the majority for their extremism and unwillingness to compromise on what mattered most. The Bible, cover to cover, is full of their stories. In the days of the Church, the pattern continues. Roger Williams is one such example.

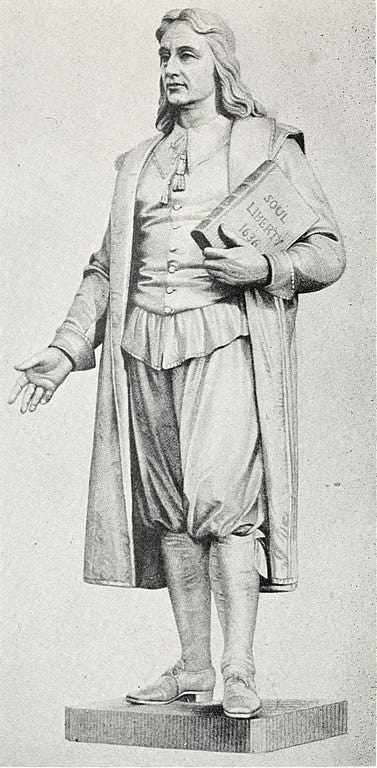

His life

Roger Williams, born in London around 1603, was almost your typical Puritan colonist in 1600s New England: fed up with the Church of England and hoping for a better life in the great unknown, he boarded a boat bound for Boston as a young man ready to start a family with his wife Mary Bernard, the daughter of a prolific Puritan preacher. He had a knack for languages, having studied Greek and Hebrew at Cambridge, and was offered a position in the church at Boston as soon as he arrived.

However, this was not to be. Like the other Puritans, Williams was concerned with religious freedom. Unlike the others—indeed unlike almost everyone in the 1630s West—he believed in the ideal of religious freedom for even those he disagreed with. The idea that a government or church would prosecute citizens for something like breaking the Sabbath, or that people would not be free to follow their own conscience, was a dealbreaker for him. Williams held unwaveringly to his convictions and realized the church at Boston was not as separate from the authoritarianism back home as he might have hoped, and so he declined.

Williams was searching for a church with pure worship, a primitive church that reflected the unconditional love of Christ the way the early church did, a church that asserted true doctrines while protecting the freedoms of all, whether Christian, heretic, pagan, Jew, settler, or indigenous. He would be searching for the rest of his life.

At first, it seemed like he might be able to fit in somewhere; after all, there were plenty of Separatists in New England. Williams went to Plymouth and preached for a time, but he was concerned that they had not sufficiently separated from the Church of England and that the natives had been treated unfairly in land agreements. These “strange opinions,” according to Governor Bradford, began to cause a stir.1

It came to a head in 1632 when Williams wrote a polemical tract and decried the king and his charters; since, in Williams’ view, “states had nothing to do with real Christianity, it was ‘blasphemous’ for European monarchs to call themselves Christian monarchs.”2 He went to Salem, was brought to trial, and the tract was lost to history (probably burned by his dissenters). He managed to preach in Salem for a while, but continued to be summoned to court for his dangerous opinions and the church was ordered to depose Williams. Lacking support, he resorted to preaching in his home until he was convicted of sedition and heresy and banished from Massachusetts in the winter of 1635.3

Williams tried to live by the convictions he had been exiled for. After making an agreement with Native Americans, a people group with whom Williams forged deep friendships and trust throughout his life, he established a settlement called Providence Plantations in what is now Rhode Island.4 Other exiles and families embittered with Massachusetts leadership flocked to the settlement,5 and a brave new mode of government was established: one founded on liberty of conscience that only dealt with civil matters and was separate from the church. They planted a church too, of course—known today as the First Baptist Church in America.6

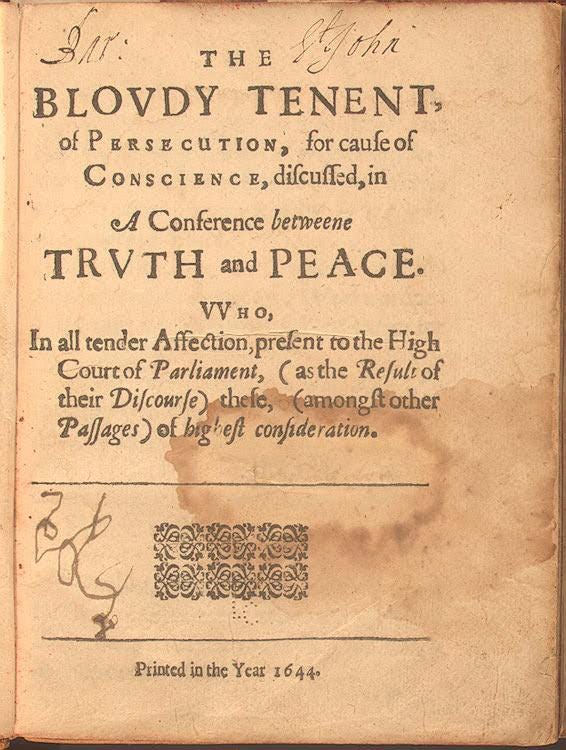

Williams spent his years preaching, working, and mediating between colonists and natives, as well as a temporary return trip to the Old World where he published the highly controversial The Bloudy Tenent [Bloody Tenet] of Persecution for Cause of Conscience, which called for a separation of church and state and declared religious freedom a God-given right, going so far as to profess that Constantine and his ilk “did more hurt to Christ Jesus’s crown and kingdom, than the raging fury of the most bloody Neros.”7

Despite the commotion, he managed to return to Rhode Island and participate in building a world in which Baptists, Quakers, and Jews alike could live in peace. After many hardships, including having his home burned during a war with Native Americans he tried to prevent, Williams died quietly in 1683.

His doctrine

Williams remained active in the church throughout his life, but he mourned what he believed to be its fallen state. The church was at its most holy when Christians faced persecution, which made them “sweet and fragrant, like spice pounded and beaten in mortars. But these good emperors [Constantine et al], persecuting some erroneous persons, Arius, &c., and advancing the professors of some truths of Christ—for there was no small number of truths lost in those times—and maintaining their religion by the material sword—I say, by this means Christianity was eclipsed, and the professors of it fell asleep…Babel, or confusion, was ushered in, and by degrees the gardens of the churches of saints were turned into the wilderness of whole nations, until the whole world became Christian, or Christendom”.8

Despite his strong words for national churches, Williams made it clear he wasn’t condemning the many legitimate Christians participating in them. For Williams, since the “line of apostolic authority was broken in the fourth century, Christians had been left with no means of forming themselves into legitimate congregations.”9 Although many Christians through the centuries were mired “in a Babilonish dunghill,” they were still “Jewels most precious to him” and “his Lillie[s] sweet and lovely in the Wildernes commixt with Briars”; for God would not lose His own in “Egypt, Sodome, [or] Babel”.10

Legitimate Christians or not, to experience pure worship required recognizing the fallen state of the church and repenting of one’s participation in its brokenness, seeking to restore it sans “inventions of men that have clouded the divine pattern.”11

To get “neerest to Christ” required rejection of not only the broken, authoritarian elements in the modern church, but also contentedness with the inevitable “poor and low condition in worldly things” that would follow. Furthermore, there was no room in Christ’s church for “smiting, killing, and wounding the Opposites of their profession and worship, that they resolve themselves patiently to bear and carry the Cross and Gallows of their Lord and Master, and patiently to suffer with him.”12 After all, this imitates Christ who “was a glorious king, mighty and full of splendor, but only in his spiritual kingdom”.13 When coming to share in our humanity, Christ “disdained not to enter this World in a Stable, amongst Beasts, as unworthy the society of Men: Who past through this World with the esteeme of a Mad man, a Deceiver, a Conjurer, a Traytor against Caesar, and destitute of an house wherein to rest his head”.14 For Williams, “one prime mark of the true church was that it was always a suffering church.”15

When power comes one’s way, the true believer would have little to do with it. “The neerer Christs followers have approached to worldly wealth, ease, liberty, honour, pleasure, &c. the neerer they have approached to Impatience, Pride, Anger and Violence against such as are opposite to their Doctrine and Profession of Religion: And (2) The further and further have they departed from God, from his Truth, from the Simplicitie, Power and Puritie of Christ Jesus and true Christianitie.”16 We cannot grasp worldly power and use it to condemn others, for neither did Jesus (John 12:47). Williams instead appealed to passages like 2 Cor 10, Eph 6:10-20, and 2 Tim 2 to suggest that the weapons Christians should wield are spiritual ones.17

Our response

In the nearly 400 years since William’s life ended, his radicalism has been interpreted in different ways. “The early Victorian apologists for the Massachusetts Bay Puritans considered Williams to have been somewhat unpleasantly eccentric, but throughout the first half of the twentieth century, at least, everyone who looked at Williams saw a pioneer of liberal democracy, an irrepressible democrat who foreshadowed all the modern political virtues.18 Only in 1953 did Perry Miller break with that consensus and depict Williams as a pleasantly eccentric interpreter of the types and antitypes of Scripture,19 a depiction that Edmund Morgan reinforced in 1967 with his lucid account of Williams as a man securely ensconced within the seventeenth century rather than the nineteenth.20 To some extent, [they] prepared the way for us to accept Leonard Allen’s further contention that, in some respects, Williams was a man of the first century, not simply of the seventeenth.”21

How do you see Roger Williams? I myself am a man of the twenty-first century; like Williams, can I not also be a man of the first?

Gaustad, E.S. 1999. Liberty of Conscience: Roger Williams in America. Judson Press. Pg. 28.

Winship, M.P. 2018. Hot Protestants: A History of Puritanism in England and America. Yale University Press. Pg 97.

Ibid, pg 99.

Conley, P.T. 1985. An Album of Rhode Island History. Donning Company.

Winship, M.P. Hot Protestants. Pg 108.

King, H.M. & Wilcox, C. F. 1908. Historical Catalogue of the Members of the First Baptist Church in Providence, Rhode Island. Townsend, F. H., Printer.

Williams, R. 1644. The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience. Ch. LXIV. At the time of writing, the book can be found for free here thanks to Project Gutenburg.

Ibid.

Allen, C. L. 1988. Roger Williams and “the Restauration of Zion”. In: Hughes, R. T. (ed.) The American Quest for the Primitive Church. Pg. 41.

Williams, R. 1644. Mr. Cottons Letter Lately Printed, Examined and Ansvvered.

Allen, C.L. Roger Williams and “the Restauration of Zion”. Pg. 36.

Williams, R. 1652. The Bloody Tenent Yet More Bloody.

Allen, C.L. Roger Williams and “the Restauration of Zion”. Pg. 37.

Williams, R. Mr. Cottons Letter Lately Printed, Examined and Ansvvered.

Allen, C.L. Roger Williams and “the Restauration of Zion”. Pg. 37.

Williams, R. 1652. The Bloody Tenent Yet More Bloody.

Byrd, J. P. 2002. The Challenges of Roger Williams: Religious Liberty, Violent Persecution, and the Bible. Mercer University Press.

Brockunier, S. 1940. The Irrepressible Democrat: Roger Williams. Ronald Press.

Carpenter, J.E. 1909. Roger Williams. Grafton Press.

Hall, M.E. 1917. Roger Williams. Pilgrim Press.

Easton, E. 1930. Roger Williams: Prophet and Pioneer. Houghton Mifflin.

Ernst, J.E. 1932. Roger Williams: New England’s Firebrand. Macmillan.

Miller, P. 1953. Roger Williams. Atheneum.

Morgan, E. 1967. Roger Williams: The Church and the State. Harcourt, Brace.

Holifield, E.B. 1988. Puritan and Enlightenment Primitivism: A Response. In: Hughes, R. T. (ed.) The American Quest for the Primitive Church. Pg. 71.