Learning from our spiritual heritage: Means and ends

What do a Tennessean farmer, a Ukrainian Jew, and a French sociologist have in common?

Whoever destroys a single life is considered by Scripture to have destroyed the whole world,

and whoever saves a single life is considered by Scripture to have saved the whole world.

— Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:5

These words come from the Talmud,1 but they were inspired by the divinely inspired Word of God. According to many in the broad Judeo-Christian tradition,2 these words are the distilled essence of the entire Bible. What do they mean? If these words truly summarize the Word, what do they say about how to pursue a virtuous life?

This Talmudic principle can be gleaned from the Bible as early as the first chapters of the Torah according to its author. Humanity was created from one man, Adam, so no one’s father is better than another and we are all of equal worth, and the killing of any child of God is like the extinguishing of an entire race just as Cain’s first murder destroyed a righteous line that would never be.3

Indeed, Christians must understand that the principle was proved correct in an infinite sense when the resurrection of one Son of Man extended salvation to all the rest.4

Beyond Genesis, the Bible continually promotes an other-first ethos guided less by practical, measurable self-preservation and more by the freedom to do what is right granted by the belief in an all-powerful God who promised to take care of you. In Leviticus and Deuteronomy we find the words later repeated by Jesus as the hinge pins of the Law,5 and throughout the stories of Israel’s history we learn that the world’s ways of protecting a people are not God’s ways and God’s people err when they place faith in the former.

In Shabbat, another part of the Talmud, there is an interesting story about Hillel the Elder, who died only a few years before Jesus was born in Bethlehem:

There was another incident involving one gentile…who came before Hillel. He converted him and said to him: That which is hateful to you do not do to another; that is the entire Torah, and the rest is its interpretation. Go study.

— Shabbat 31a

Of course, our beloved Jesus can sum up the Word of God more perfectly than any of us because he is the Word.6 The world continues to be astonished at God’s teaching whenever it is practiced by those who love him:

And one of them, a lawyer, asked Jesus a question to test him. “Teacher, which is the great commandment in the Law?” And he said to him, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets.”

— Matthew 22:33-407

It’s pretty simple despite traditional, institutional Christianity’s continued inability to practice or even preach it.8 Once you love the true God, you are freed9 from having to worry about what works and doesn’t work, what is effective and what isn’t, what makes sense and what doesn’t. You’re freed, in one sense, from the repercussions of your acts—from repercussions you never controlled in the first place. You’re freed from the slavery of ends and allowed to think only in means.

In other words, you can rest in the faith that God will take care of you in the ways that truly matter and the story will end in the way he wants it to. Instead of thinking like the world and justifying your acts now by the end it will hopefully achieve, you can focus on doing by your neighbor what is right and loving without fear.

The world must think of the greater good, and it will justify whatever is necessary for its sake. The end shall justify the means.

But this is only true under the sun, only true outside of Christ. Those who have ears to hear, let them hear.

Although mainstream Christianity regularly forgets this and tries to bring about the kingdom of heaven through worldly means,10 there are many in our Judeo-Christian heritage who remind us of our God-given role and point us back to the living-out of God's Word.

I’d like to highlight three: David Lipscomb, Rabbi Abraham Judah Heyn, and Jacques Ellul.

These men never knew each other and came from three distinct backgrounds, spoke three different languages, participated in three religious traditions, and one of them even disagreed on the one thing that truly matters—the person of Jesus Christ—but they had one important thing in common. They believed that God made the means of discipleship, or following God, our concern and freed us from worldly concerns of ends like efficacy or the greater good.

Or again, in other words: to love one neighbor is to love them all; to hate one neighbor is to murder them all.

“The justification of the means considered in themselves is a fundamental principle of Judaism, its primary substance. This is one of its most revolutionary contributions to world culture. The tool which the hands operate, must itself be perfect…any blemish, no matter how small, invalidates it…the whole idea of absolutely despising a transgression performed by way of a good deed, that whole system, is the novel contribution of Judaism…[which] represents the opposite extreme of the idea that the ends justify the means.”

— Abraham Judah Heyn

11Rabbi Abraham Judah Heyn12 was born in Chernihiv in 188813 to a family steeped in Hasidic Judaism, today an obscure figure despite his active involvement in Judaism as a Rabbi throughout Europe as he fled the Soviet Union and eventually landed in Palestine and Jerusalem.14 In the quote above, he is recognizing that Jewish kosher law is in one respect an extension of the biblical ethos of means and ends. The tool matters.15

Thinkers like Heyn, although they may not agree with you or I on the nature of Christ, are important because they remind us in a practical manner that Jesus came to fulfil the law and not abolish it;16 when Christians like Lipscomb and Ellul point out this aspect of Jesus’ message, they are saying nothing new. Even before Christ when only the Old Testament provided access to the inspired Word of God, this idea could be found.

It’s an offensive idea that ends might not justify means. If we recognize this as part of the biblical ethic, then our perspective on the Augustinian tradition of just war shifts dramatically. Our understanding of every aspect of politics and governing is turned on its head. Our own internal decision-making and discernment changes, and what we might have justified for the sake of the greater good now becomes offensive to us.

It’s not that there isn’t some greater good we should care about but rather that when we participate in immoral acts or use people or systems that hurt others, we profane our own goal. Hayyim Rothman summarizes Heyn’s view: if “the means are bad, their result will be bad; means must accord with their end and in this sense constitute ends in themselves.”17

“To use the human is to reject Divine wisdom and divest ourselves of Divine help. To use the Divine is to follow Divine wisdom and to seek and rest upon Divine help. There can be no doubt as to which is the Christians duty. Then the Christian most effectually promotes public morality by standing aloof from the corrupting influences of worldly institutions.”

— David Lipscomb

David Lipscomb was born in Huntland and lived in the Central Basin of Tennessee, the same region that I have lived my entire life in, and was a farmer and preacher in the same stream of Christian tradition that I participate in.

It’s safe to say I’m partial to the guy for those reasons alone, but his perspective on means and ends is unfortunately increasingly relegated the past in my tradition18 and bears repeating. In wreckage and aftermath of the American Civil War, Lipscomb’s understanding of how God calls his disciples to witness to the world was radically altered. Although the term “anarchist” is less applicable to Lipscomb than to Heyn,19 their understanding of means and ends was similar.20 To use God’s ways is to rest in faith in God. To use man’s ways—force, subjugation, slavery, coercion, centralization—to achieve what we believe are God’s ends is idolatry.

For Lipscomb, as well as Heyn and Ellul, this reality has a directly political application. No matter the extent to which God placed human authorities and governments in control for the sake of order in a fallen world, the means of these rulers is not a means available to a disciple of Jesus. John Mark Hicks, a theological scholar at Lipscomb University, summarizes David Lipscomb’s view:

But are not human governments ‘ordained’ of God, according to Romans 13? Lipscomb agreed. Human governments are ordained as servants of God for the punishment of evildoers, just as Assyria and Babylon were ordained to punish Israel and Judah for their sins. Nebuchadnezzar and Nero were ‘servants of God’ in this sense, but no Christian can serve as they served because Romans 12 forbids disciples of Jesus to participate in acts of vengeance and strife. Christians do not return evil for evil but give a cup of cold water to their enemies.21

Although Lipscomb didn’t use the language of means or tools, the gist of the underlying principle is the same. Where the means are unholy, the Christian exhibits a lack of faith in resorting to them. He took this principle far enough to even question the act of voting itself, saying “dependence on civil government for help or success in this work [of the kingdom of God] is treason.”22

“We must not think about ‘human beings’ but about my neighbor Mario. It is in the real life, which I can easily come to know, about this particular person, that I see the true repercussions of the machine, the press, political speeches, and government. I may be told that things are different for a farmer in Texas or for a Kolkhozian, but I know nothing about that (and news reports are not what will inform me), and I have my doubts, because I believe in a human nature.” — Jacques Ellul

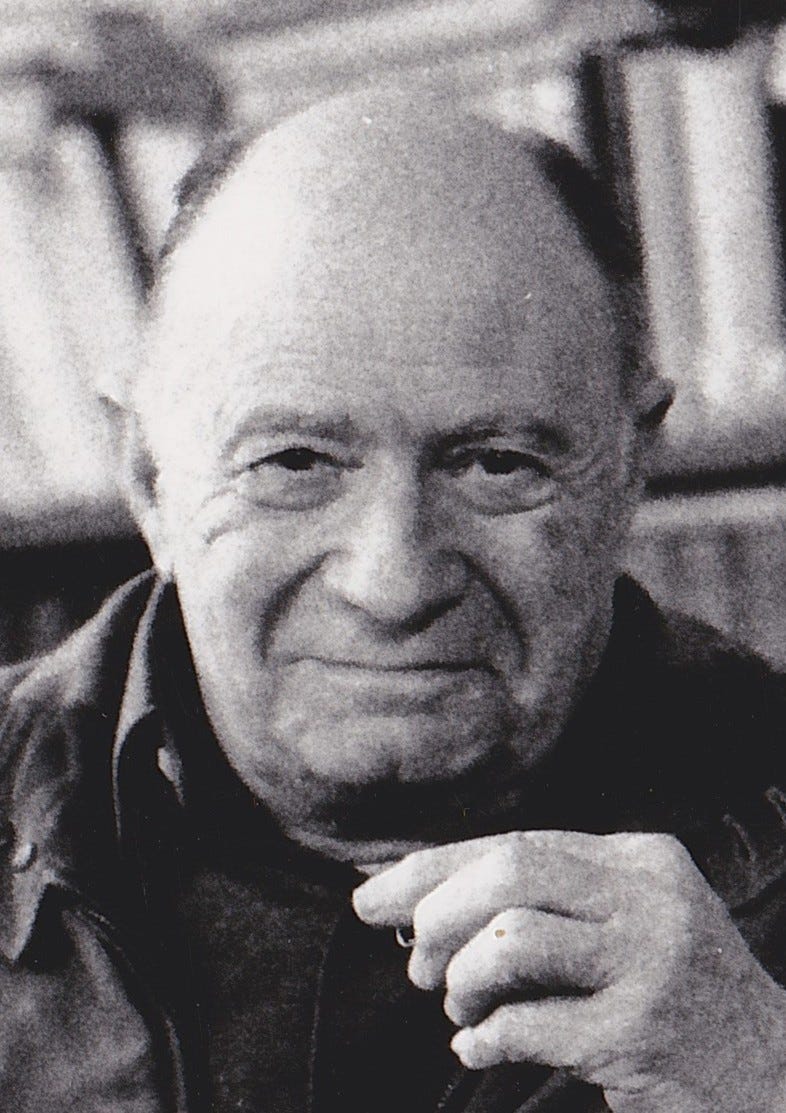

23Jacques Ellul, born in Bordeaux in 1912, was a trained sociologist and an expert on Roman law known for his critiques of the modern world, but he also made a name for himself as a theologian and philosopher. He came from the Reformed tradition but his views were nonstandard and have had a significant impact on the way I think.

In the quote above, we already see how closely his idea of virtuous praxis has little to do with the greater good and everything to do with a high valuation of every human life—just like Heyn and Lipscomb. Unlike the former two, however, Ellul spent a great deal of time applying the specific language of means and ends to his perspective. In serving an all-powerful God, in following Christ who is the only one who can provide meaning to our acts in this vain life under the sun, we are freed and bound to act in a manner distinct from the world as we seek to build the kingdom of God on its cornerstone:

The first truth that must be recalled is that for Christians there is no separation between means and ends…

What counts are not our instruments and institutions, but ourselves, because it is we ourselves who are God’s instruments. And because the church and all its members are God’s means, they must be this presence of the end that characterizes the kingdom. So we need never seek an objective external to ourselves, which would have to be attained at the cost of great effort (all efforts are accomplished in Jesus Christ!). Instead, we must bear within ourselves the objective toward which God is orienting the world. Regardless of whether we like it or whether others call it pride, Christians are not in the same situation as others concerning this end: they have received this end within themselves through God’s grace. They must represent before the world this unity of end and means, of which Jesus Christ is the guarantor. For human beings are not the ones who establish this end as such or who bring it into being. It is God who determines and realizes it.24

The offensive nature of such a view is intrinsic, for how could the world accept our denial of their methods when we accept that their desired ends—peace and equality and prosperity for all—are good?

So it is the fact of living, with all its consequences, all its twists and turns, that is the revolutionary act par excellence and also the answer to this problem of end and means. In a civilization that no longer knows what life is, the most useful thing that Christians can do is precisely to live, and the life held in faith has a remarkably explosive power. We no longer realize it, because we no longer believe in anything but efficiency, and life is not efficient. But it—it alone—can provoke the astonishment of the modern world by revealing to everyone the ineffectiveness of techniques.25

Like Heyn, Ellul found this message even in the Old Testament. He makes the case that Jehu, one of the kings of Israel with a complicated story, is a prototypical example of someone who was faithful to God but foolishly believed that he could justify his own methods of achieving God’s goals.26

Jehu is the prototype of demiurgic politics. The whole question may in fact be reduced to two points—the inner attitude, and the choice of means.

We are always tempted to think that all means are good once they are subjected to the will of God (inwardly) or oriented to the end that God seeks. We fail to see that this always amounts to the fallacy that ‘the end justifies the means,’ and we justify ourselves hypocritically by invoking the dictum that ‘to the pure all things are pure.’ In fact, as these stories have progressively shown, the choice of means is our great responsibility. All means are not good in doing God's work.27

I think Christians—including myself—fall prey to the idolatry of placing faith in the world’s methods. We are in the world, we cannot and indeed should not avoid entirely participating in the world’s ways, but equally we must never put our faith in these ways. We must always remember where is Babylon. The full extent of this idea is staggering and humbling, forcing us to turn back to Jesus’ victory on the cross and the grace which is our only method of navigating this world.

To the extent we recognize that it is Jesus who accomplishes all that matters, to the extent we recognize that the Holy Spirit has a different understanding of effectiveness than the world, we can rest and worry not about how foolish the world perceives our actions to be.

The action we attempt will always be regarded by the world as a failure, and the more so the more it is authentically faithful. We cannot be successful or show the church to be effective in the world unless we adopt the world's criterion of efficacy, which means adopting its means as well.

As the world sees it, action which is faithful to God will always fail, just as Jesus Christ necessarily went to the cross. Such action always leads to a dead end. It is always a fiasco from the standpoint of worldly power. But this should not worry us. It does not mean that our action is in truth ineffectual. Efficacy measured in terms of faithfulness cannot be compared at any point with efficacy measured in terms of success…

Yet it is no less real.28

This message need not be disheartening, however. How can we have hope knowing our inevitably worldly methods will inevitably fail? Because God gives our acts meaning if we have faith. He makes them relevant to his greater plan.

No matter how strong our resolve, our means are still the means of the world and they will always participate to some degree in the world. They thus have a hold over us…Even Solomon could not resist being an oriental monarch when he used the means appropriate thereto. Only the presence of the Wholly Other at the heart of our action cannot be assimilated by sociological forces. It alone is the guarantee of our independence. It evades both society's grip and also our own.29

It’s an impossible message to convey that destroys our wisdom and frustrates our intelligence.30 But it seems to be the biblical message that God’s ways are not our ways, regardless of how we agree or disagree on its application in our lives. And we have a rich heritage of those gone before who, despite fallibility, radically point us back to grace and faith in what matters.31

“The means chosen by God has no meaning for man’s projects. But it is the only means. And we must never stop saying this, for God has not resigned himself to man’s refusal.”

— Jacques Ellul

You might also recognize them from the 1993 film Schindler’s List.

It may be that this principle is best described not as the product of the Judeo-Christian heritage but rather more broadly as the product of the Abrahamic heritage. The idea is actually found in the Quran (Sura 5:32). I don’t know enough about Islam to deal intelligently with this but I wanted to acknowledge it. For an entry-level discussion on this and the related issue of whether Mishnah 4:5 originally referred to any human life or just Jews, see this article from Philologos.

It should also be acknowledged that the golden rule appears in many religions in various forms. For the Christian, this is another in a plethora of examples in which even the pagans to varying degrees have pointed to the coming of Christ.

Gen 1-4, Matt 23:35.

1 Cor 15:12-20.

Lev 19:9-18, Deut 6:4-9, Matt 22:34-40.

John 1, cf. Heb 1:2.

ESV. Cf. Matt 7:12, Gal 5:14.

Although I do mean this as a slight, understand that I am not saying we shouldn't participate in traditional, institutional Christianity. I do. We should. But where Christians have regularly erred, we should be a voice of dissent.

John 8:31-39, 2 Cor 3:17, Gal 5:1.

This quote is from Be-Malkhut ha-Yahadut: Pirke Hagut u-Mahshava, Vol. 3, 318. The passage can be found in English, along with some commentary, in pg 35 of Abraham Heyn’s Jewish Anarcho-Pacifism by Hayyim Rothman, in Essays in Anarchism and Religion: Volume III. Christoyannopaulos, A. & Adams, M.S. (eds.). Stockholm University Press, 2020. At the time of writing, this article is available here.

Heyn’s posthumous three volume work, in English In the Kingdom of Judaism: Meditations and Thoughts, has been compared to Tolstoy’s political theology, especially The Kingdom of God is Within You. For some discussion on this similarity along with other Jewish thinkers, see The Jewish Inheritors of Tolstoy: Judah-Leyb Don-Yahiya, Abraham-Judah Heyn, and Nathan Hofshi by Hayyim Rothman. At the time of writing, this article is available here.

You might also see his name transliterated as some variation of Avraham Yehuda Khein, but I’ll use what I assume to be a more American spelling. What a dope-sounding name, by the way.

The sources I read for this article have various dates for his birth. 1888 is the date used in Rothman’s essay.

Rothman, Abraham Heyn’s Jewish Anarcho-Pacifism, pg 26.

This has a directly political connotation, which is part of the impetus for this article. Also consider Exod 20:25.

Matt 5:17.

Rothman, Abraham Heyn’s Jewish Anarcho-Pacifism, pg 35. Some additional reading on the extension of this idea to political principles is provided in the footnotes on pg 35-36.

This article will focus on the high points of Lipscomb (and the other men’s) views, but that’s not to say they weren’t problematic in other ways. One great resources that explores Lipscomb’s political theology and considers its faults is Resisting Babel: Allegiance to God and the Problem of Government edited by John Mark Hicks, which I’ve also referenced in these three articles.

The question of anarchist and other labels in regard to Lipscomb is addressed in Peaceable Pilgrim or Christian Anarchist: David Lipscomb’s Political Theology by Richard C. Goode in the aforementioned Resisting Babel (see footnote 19).

I mention this only because discussion on means and ends is pivotal to most streams of anarchist thought and because the label of anarchist has been widely applied to Heyn and Ellul. The Restoration Movement, especially in its modern forms, is not generally associated with that label but enough overlap in ideology is present to warrant comment.

Hicks, Resisting Babel: Allegiance to God and the Problem of Government, pg 46.

Ibid, quoting Can Christians Vote and Hold Office? Rejoinder I by Lipscomb in 1881. Cf. Matt 6:33.

Jacques Ellul, Presence in the Modern World: A New Translation, pg 79. Wipf and Stock, 2016. Translated by Lisa Richmond.

Ibid, pg 51-52.

Ibid, pg 61.

1 Kgs 9-10.

Jacques Ellul, The Politics of God and the Politics of Man, pg 116. Wipf and Stock, 2012. Translated by Geoffrey W. Bromiley.

Ibid, pg 139-141.

Ibid, pg 142.

Cf. 1 Cor 1:19.

Final quote from The Meaning of the City by Jacques Ellul, pg 171. Wipf and Stock, 2011. Translated by Dennis Pardee.

"They believed that God made the means of discipleship, or following God, our concern and freed us from worldly concerns of ends like efficacy or the greater good."

I loved this so much, the way you find connections between seemingly disparate ideas.