This concludes an informal trilogy on what it means to live and what it means to be free, and how preposterous the truth is.1 There are brighter subjects ahead, for one can only meditate on death for so long. Surely it’s far from the last time I’ll quote Romans 6-8, but this trilogy may be the last time for a while they get referenced in such dire contexts.

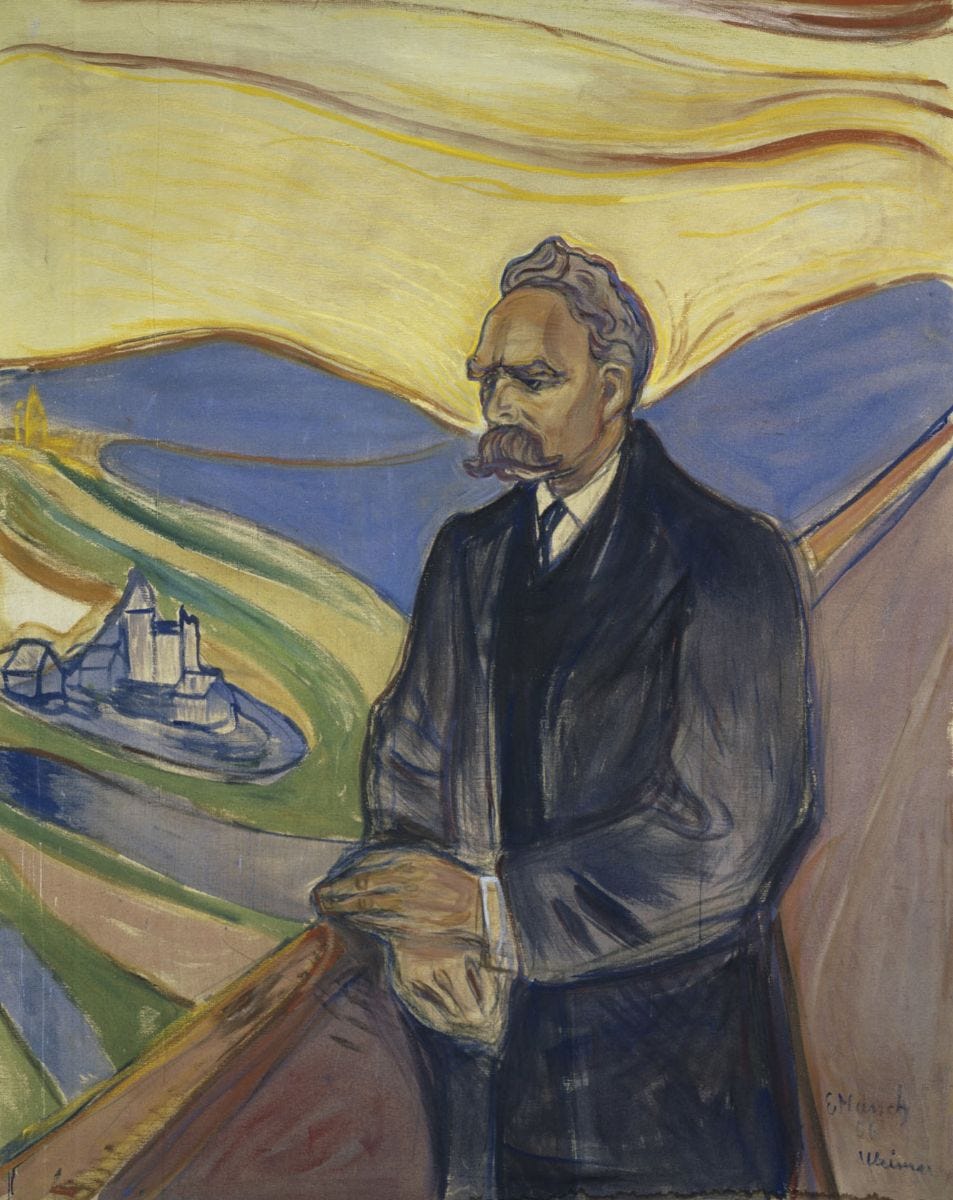

Anyway, if you can stomach one more needlessly externally-dependent text: here’s why the world is both more right and more wrong about the Bible than they realize—with a little help from Friedrich Nietzsche.

“You call yourself free? Your dominant thought I want to hear, and not that you have escaped from a yoke. Are you one of those who had the right to escape from a yoke? There are some who threw away their last value when they threw away their servitude.

Free from what? As if that mattered to Zarathustra! But your eyes should tell me brightly: free for what?”

Thus spoke Zarathustra, or, Friedrich Nietzsche,2 who ranges from the boogeyman of Christendom to the most prominent preacher of humanism and accelerationism, depending on who you ask. Really, he was something in the middle: a mediocre philosopher with words wrapped in gilt just confusing enough to be beautiful, just sane enough to be appealing. Well, somewhat sane. At this point in his life anyway. His sanity faded as he aged.

He had two things going for him, two things that make him valuable for Christians to read: he took the Bible seriously, and he elucidated exactly what secular humanism believes when boiled down to its salts. Put another way: he realized that the teachings in the Bible, or at least the New Testament (he failed to recognize congruity between the two), were incompatible with the basic tenets of secular, progressive humanism.

And yes, that’s a fitting descriptor to apply to Nietzsche. The idea that Nietzsche was a nihilist is preposterous—he was an optimistic progressive accelerationist who thought humans were going somewhere. He was a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed builder of Babel, which makes him exactly like most adults on planet Earth.

“May I give birth to the overman!”

— Nietzsche

He would, ironically—and knowingly so—call me a preacher of slow death. You see, I preach what I believe—and Nietzsche believed—that Jesus modeled. That the only way to be free is to willingly become a slave, and that the only way to be alive is to willingly enter into death, and that the only way to be an individual is to become part of a collective called the body of Christ. That it’s never ok to do evil to someone in the name of grander human agendas. A lonely path relying entirely on faith in the One who said if I seek, I will find.

“‘He who seeks, easily gets lost. All loneliness is guilt’—thus speaks the herd. And you have long belonged to the herd.”

— Nietzsche

He asks, free from what am I? Free for what? Don’t tell me you’ve escaped from a yoke, you fool!

No, I’ve submitted to one. A yoke of freedom. A yoke that is easy and light.

For freedom Christ has set us free; stand firm therefore, and do not submit again to a yoke of slavery.

— Galatians 53

To avoid walking in circles, here’s the deal: everyone, including you and I (I’m trying to get myself out of this category but I haven’t managed it yet), obeys the worldly wisdom of the greater good. That we are called to do otherwise is one of the most fundamentally offensive aspects of the Bible.

It’s ironic because as much as we worship this murky utilitarian ideal, we equally hijack it to make it serve our selfish, temporal, pointless personal ends. In attempting to be obedient to something external, to be imitators of some model, we end up only worshipping ourselves. Basically we do whatever we want, except it isn’t what we want deep down, and we justify it by pretending it’s “for the best.” This describes us all to some degree, and Nietzsche was someone willing not only to admit it, but to make it an ideal.

I don’t want to give the wrong impression of Nietzsche; I really think he spots something real in the Bible that even most Christians don’t. But that doesn’t make him any less wrong. What I’m getting at is that most people actually agree with Nietzsche here: we must sweep aside the weak for the sake of something greater.

Belief in the greater good as something that we can strive for on a morally and historically justified basis is fundamental to human society. Countless people of all stripes have written about or alluded to this—Melville is one I’ve discussed recently.

In ceasing to strive for the greater good, indeed in condemning such striving altogether, one becomes the enemy not just of powers and states, but of all society. Truly, at that point the only remaining non-enemy is God. This is acceptable because in naming God as the enemy of last resort one actually names Him as one’s first love, for the last shall be first. As for the naivety in doing the good before me I know I ought to do—when all the while more pressing matters are left unstriven for—I cannot deny its foolishness or its certainty in making enemies daily. But love believes all things foolishly. Perhaps in neglecting the greater good I work toward it—no, I mean it is achieved already by Another.

But I am rambling. I am a preacher of slow death, a title attained according to Nietzsche by preaching the fastest death:

For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.

— Romans 6

“Many die too late, and a few die too early. The doctrine still sounds strange: ‘Die at the right time!’

Die at the right time—thus teaches Zarathustra. Of course, how could those who never live at the right time die at the right time? Would that they had never been born! Thus I counsel the superfluous. But even the superfluous still make a fuss about their dying; and even the hollowest nut still wants to be cracked. Everybody considers dying important; but as yet death is no festival.”

— Nietzsche

You see, in attempting to do the good that is before us—to be as the good Samaritan, and not the priest or Levite—to give the two copper coins and not the merciless riches—to be concerned with the ecology of your backyard rather than the distant lands politicians procure your assistance with—to be concerned with your nextdoor neighbor Mario instead of distant Texans or Kolkhozians—to think always of the eternal instead of the temporal, even the temporal future we supposedly seek—we become arsonists of Babel. We become loathsome murderers of earthly gods. Preachers of a slow death to all that is loved by the world.

We become followers of that One who, said Nietzsche, would have recanted if given time to mature:

“All-too-many live, and all-too-long they hang on their branches. Would that a storm came to shake all this worm-eaten rot from the tree!

Would that there came preachers of quick death! I would like them as the true storms and shakers of the trees of life. But I hear only slow death preached, and patience with everything ‘earthly.’

Alas, do you preach patience with the earthly? It is the earthly that has too much patience with you, blasphemers!

Verily, that Hebrew died too early whom the preachers of slow death honor…the Hebrew Jesus.

…He died too early; he himself would have recanted his teaching, had he reached my age. Noble enough was he to recant.”

— Nietzsche

Nietzsche was starved of the eternal plane, blind to it and thus a slave to some craving he could not understand. One craves the eternal, so he supplanted it with his silly Overman. Like all progressives and accelerationists, he is as much a fool as I am. Man cannot give birth to the Overman or cross the infinite qualitative abyss on a tightrope.

He ends with words that ring with truth. As with many thoughtful pagans (Socrates, Diogenes, Epictetus, to name a few), the language itself translates almost directly to biblical reality. But the meaning must be radically transposed if truth is to be found:

“But in the man there is more of the child than in the youth, and less melancholy: he knows better how to die and how to live. Free to die and free in death, able to say a holy No when the time for Yes has passed: thus he knows how to live and die.

That your dying be no blasphemy against man and earth, my friends, that I ask of the honey of your soul. In your dying, your spirit and virtue should still glow like a sunset around the earth: else your dying has turned out badly.

Thus I want to die myself that you, my friends, may love the earth more for my sake; and to earth I want to return that I may find rest in her who gave birth to me.”

— Nietzsche

As a hanger-on and flawed disciple of that outmoded ethic of pity and compassion and neighbor-love, even at the expense of the greater good, I believe that the following words of Nietzsche apply not just to himself, but to virtually everyone on earth who is more wise in the ways of the world than I am:

“‘And what, O Zarathustra, is the moral of your story?’ Then Zarathustra answered thus:

The annihilator of morals, the good and just call me: my story is immoral.”

— Nietzsche

If I am wrong, then I am to be pitied above all others—except that if I am wrong, pity isn’t a virtue. So don’t bother.

if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain…if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile…If in Christ we have hope in this life only, we are of all people most to be pitied.

— 1 Corinthians 15

If we have hope in this life only, then we must be pitied because we are preachers of death and we are terrorists of civilized society. On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that many Christians are doing quite well in this life by any standard and find themselves contributors to the greater good in equal part alongside the world’s most vehement humanists and progressives. But I have only so many stones to throw at a time.

The other parts being How to be yourself and Booleans and shades of grey.

All quotes from Nietzsche in this post are from Thus Spoke Zarathustra: First Part, as translated by Walter Kaufmann, specifically from the consecutive sections On the way of the creator, On little old and young women, On the adder’s bite, On child and marriage, and On free death.

Bible quotes are in ESV.

"If I am wrong, then I am to be pitied above all others—except that if I am wrong, pity isn’t a virtue. So don’t bother." Made me smile.

Well developed thread and a zinger of an ending. I feel kind of sorry for the cranky old man N.