Brief Ruminations: Edom as Rome in rabbinic literature

Why might Israel's ancient sibling nation be identified with evil imperial powers like Rome and Babylon?

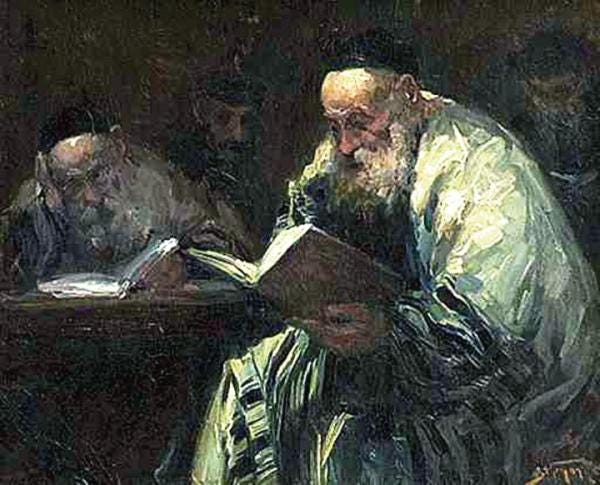

Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Yosei and Rabbi Shimon were sitting, and Yehuda, son of converts, sat beside them.

Rabbi Yehuda opened and said: “How pleasant are the actions of this nation, the Romans, as they established marketplaces, established bridges, and established bathhouses.”

Rabbi Yosei was silent.

Rabbi Shimon ben Yoḥai responded and said: “Everything that they established, they established only for their own purposes. They established marketplaces, to place prostitutes in them; bathhouses, to pamper themselves; and bridges, to collect taxes from all who pass over them.” — B Shabbat 33b

Brief Ruminations: Edom as a paradigm for the nations

In the short but powerful book of Obadiah, the prophet relays a prophecy from God against Edom, the nation descended from Esau, for aiding Babylon in destroying Israel. The focus is clearly on Edom, yet in verse 16 something interesting happens…

1In a previous post, we looked at some scriptures that seem to identify the nation of Edom with the other rebellious nations and their fates. There, we mostly considered some scriptures and raised questions. Now, let’s consider a similar vein of thought.

During the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD), the tensions in Judea hit another boiling point—a few decades after losing the temple to Rome—and the Bar Kokhba revolt kicked off. By this time and thereafter, some of the rabbis would identify Rome and its emperors with the checkered biblical figures of Esau and Edom, even interpreting the prophetic “two nations” in the womb of Rebekah (Gen 25:23) as referring not just to the relationship between Israel and Edom, but also Israel and Rome.2

One of the reasons this identification was made was that Edom had helped Babylon to conquer Judea. Thus Edom is linked to Babylon,3 which is linked to Rome (this latter connection can be seen in the Bible in places like 1 Pet 5:13). One piece of rabbinic literature describes Rome in an explicitly anachronistic manner:

Just as a bramble snatches at a man’s clothing, so that even if he detaches it on one side it sticks to the other, so the empire of Esau annually appropriates Israel’s crops and herds. Even before that, it pricks them with its poll tax. And even as this is being exacted, Esau’s men come to the people of Israel to levy conscripts.4

Throughout Judeo-Christian history, there has been an expectation that the elder nations5 would eventually serve the younger, and the sibling nations would be reconciled when God reclaimed them (e.g. Psa 82).

It is interesting that the New Testament identifies Christians with Edomites (Acts 15:15-19), and professing Christians throughout history have found themselves, like Rome, the abusers of Jews and other peoples. How far we have fallen!

However, God’s plan has remained the same despite His peoples’ failures to obey Him: Jacob will be a light to Esau, just as God will raise up Esau to restore Jacob to Him, all accomplished through the Anointed One. And so I submit to you a tenuous reading of Isaiah for consideration:

Behold my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen, in whom my soul delights; I have put my Spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations…“I am the LORD; I have called you in righteousness; I will take you by the hand and keep you; I will give you as a covenant for the people, a light for the nations, to open the eyes that are blind…”And now the LORD says, he who formed me from the womb to be his servant, to bring Jacob back to him; and that Israel might be gathered to him— for I am honored in the eyes of the LORD, and my God has become my strength— he says: “It is too light a thing that you should be my servant to raise up the tribes of Jacob and to bring back the preserved of Israel; I will make you as a light for the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth.” Thus says the LORD, the Redeemer of Israel and his Holy One, to one deeply despised, abhorred by the nation, the servant of rulers: “Kings shall see and arise; princes, and they shall prostrate themselves; because of the LORD, who is faithful, the Holy One of Israel, who has chosen you.” (Isa 42-49).

We Christians are eager to read Jesus into the passage. And He’s there—I have no wish to deny it. But what if we’re there too, as the ungodly non-Israel nations?6 Shouldn’t we rather imitate the Servant?

John Kenneth Riches and David C. Sim. 2005. The Gospel of Matthew in Its Roman Imperial Context. Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series. Vol 276, pg 31. London; New York: T&T Clark International. cf. Bereshit Rabbah 75:4, Vayikra Rabbah 15:9.

E.g. Psa 137.

Ibid, pg 32, quoting from Pesikta Rabbati 10:1.

The ancient Israelite worldview was that the nations, as a whole, rejected God prior to the creation of the nation of Israel (Gen 10-12, Deut 32:8-9).

By “we,” I’m excluding any Jewish readers who might be here.