“All-too-many live, and all-too-long they hang on their branches. Would that a storm came to shake all this worm-eaten rot from the tree!

…in the man there is more of the child than in the youth, and less melancholy: he knows better how to die and how to live. Free to die and free in death, able to say a holy No when the time for Yes has passed: thus he knows how to live and die.

That your dying be no blasphemy against man and earth, my friends, that I ask of the honey of your soul. In your dying, your spirit and virtue should still glow like a sunset around the earth: else your dying has turned out badly.

Thus I want to die myself that you, my friends, may love the earth more for my sake; and to earth I want to return that I may find rest in her who gave birth to me.”

…Thus spoke Zarathustra.

1Today, our world is obsessed with “culture.” Most of us have only a hazy, nebulous conception of such a thing, but that doesn’t stop us from fetishizing it. We call people who are educated in the tastes of society “cultured” and we go out of our way to “experience” cultures that feel alien or foreign to us. We celebrate diversity, real and imagined—although sometimes the former makes us uncomfortable—while blinding ourselves to the reality that each of us comes from a unique culture of our own. The dominant cultures have forgotten that they are such themselves, for better and for worse. This is deeply ironic, because, in our globalizing epoch, all cultures are under attack.

Ours and theirs, yours and mine, all face relentless attack and are withering away along with the accents, dialects, and languages that give them faces. There are still pockets of unashamed, honest regionalism, of beautiful, true diversity and cultural plurality, but theirs are the faces of yesterday whether we know it or not. This isn’t the result of some master plan by diabolical cabals or political interest groups; it’s merely the inevitable product of an increasingly transient society, one whose members have forgotten where they’re from. I’m not condemning it, for that would be to condemn myself. I do strive to remember, though, to be a stick in the mud.

Some cultures die and some remain, some change and adapt into something new and some do not. Culturally, as in every other way, humankind throughout history can easily be divided into conquerors and victims and their stories. But this is too simplified; these groups are never mutually exclusive. How often in our history have the victors found themselves the victims, the exploiters the exploited? To escape the latter we become the former, only for the cycle to repeat itself—if not in our own lifetimes then in the lives of our descendants.

And so our types are not so clearly defined, and history remains muddy, full of blurred lines with morality appearing only in grey smudges, smears, and spilled ink, giving rise to another type, an archetype of humanity. I like to call this type Tecumseh, after the Shawnee warrior chief who fought and died protecting his home and his people by killing Americans and yet capturing the minds and hearts of many Americans in the centuries since.

Tecumseh was one of the greatest North American orators, and one of manifest destiny’s major roadblocks east of the Mississippi. Tecumseh understood that more was at stake than the vast homelands of the native peoples: their very culture, their ways of life, were doomed to disappear if they ceded to the white man. And so he fought, and, alongside his brother Tenskwatawa the Prophet, rallied the Native Americans into one of the greatest inter-national confederate forces ever to appear on the continent. His involvement culminated in the War of 1812, where he was shot down and the alliance he fought so hard to create rapidly dispersed, and the land gradually ceded to the white man—and along with it, slightly delayed, their cultures.

Tecumseh is a legendary figure in the American consciousness, particularly in those cultures which retained elements of the land’s indigenous roots—rural America—and it can sometimes be hard to separate fact from fiction.2 Today I’m not really interested in the historical life of the man, but rather the myth himself, the larger-than-life figure. Tecumseh is the type, the paradigm, of those who realize something good is being lost to that behemoth “progress” and decide they don’t want it, that they’d rather die a stick in the mud than live without what progress takes.

And Tecumseh, like others of his ilk, died. The greatest victory is but a brief respite; Tecumseh always loses.

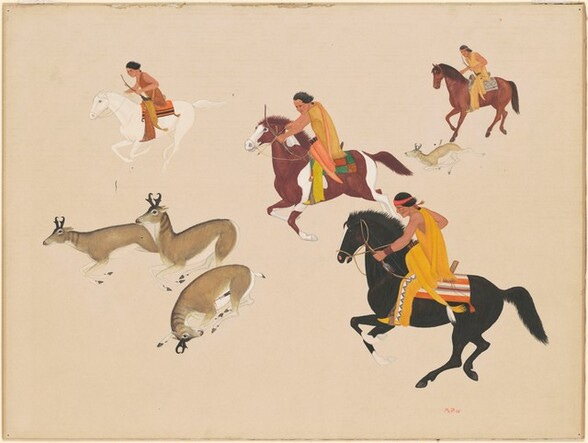

The story would play out in a remarkably similar manner just decades later west of the Mississippi, as the Plains Indians, especially Comanches—the last horse empire on earth—found themselves dealing with a new threat more belligerently heaving forward the battering ram of progress than any Mexican, Spaniard, or sedentary tribe ever had: Texans.3 Comanches, Arapahoes, Kiowas, Cheyennes, and other natives would band together under the likes of leaders like Quanah Parker4 for final stands against the onslaught of frontiersmen, pioneers, and the United States government. Many fought to the bitter end to preserve their way of life, and the fight lasted generations. But there are no free Plains Indians anymore, and no buffalo herds for them to subsist on. These Tecumsehs were laid to rest, too.

They could’ve won, actually. They had the will, skill, knowledge, and horseflesh to defeat the invaders and establish a western empire of their own, but to do so meant adapting their cultural warfare to something the white man understood, something alien to the indigenous tribes. They just weren’t interested in sieging and securing strategic locations, or extended conflicts with calculated losses, or risking the necks—and scalps—of their wives and children to maintain control, just as they weren’t interested in signing treaties that would create the possibility of a more sedentary lifestyle less destructive to their lifespans. For the most part, they were just interested in continuing to live life as they had.5

And so they fought to maintain the status quo until it was over, and the buffalo were gone, and they found themselves starving on reservations.

“The Indian became a redskin, not by loss in battle, but by accepting a dependence on traders that made necessities of industrial goods. This is not merely history. It is a parable.” — Wendell Berry

6Tecumsehs are those who realize their culture is under attack and draw a line in the sand. In North America today, the people most aware of this reality are those whose cultures still echo with faint memories of the Native Americans in their glory, the descendants of those “uncultured” peoples most capable of mingling culturally with the American world they ran toward rather than the “cultured” world they fled. Peoples with ancestral memories of the likes of Daniel Boone, whose destitution drove him to poach game in enemy territory,7 or the slave-born Holt Collier, who became one of the greatest bear hunters in the world and was thought by some to have Native American blood.8

This tale is cyclic, as we covered already. Today, Tecumsehs are the descendants of the very frontiersmen and pioneers that were once exploiters of the cultures they retain memory of and urban society has forgotten: the ones who said “here is good enough,” the “headwater-holler settlers,” in many cases the people who today are often falsely regarded as a cultural monolith under the label “rednecks” or “hillbillies.” They’re sticks in the mud, sure. But mud is life, and the more tendrils stubbornly entangled within it, the longer it lasts.

We mustn’t forget that this tendency among dominant societies to attack and conquer all, both materially and culturally, isn’t the story of humankind. It’s just the tale of the victors. Temporarily so, at that.

“To be just, however, it is necessary to remember that there has been another tendency: the tendency to stay put, to say, ‘No farther, this is the place.’ So far, this has been the weaker tendency, less glamorous, certainly less successful. It is also the older of these tendencies, having been the dominant one among the Indians.” — Wendell Berry

9You can see their awareness of the cultural winds in their10 doubling down, in their reinvigorated interest in the lives of their forefathers, in their search for unifying characteristics—even false ones—to unite them and provide a sense of identity as their heritages are slandered.11 I don’t mean to suggest that the plight of rural America is equivalent to that of Native Americans during the 1800s, but there are striking similarities: rural America, despite consisting of distinct communities with very little in common other than their distance from large cities, is truly the group with the greatest retention of Native American values in the nation (excepting the fractured remnants of the tribes themselves) and rural America is in the process of banding together as a group of sticks in the mud.

And they are losing.

They’re losing in part because they partake in the exploitation of their own values just like many Native Americans did, in part because they contribute to their own cultural demise just like the dominant culture does by fetishizing foreignness. But ultimately they’re losing because that’s Tecumseh’s fate. You can’t win this culture war. Tecumseh has an impossible task even beyond that of Sisyphus; Sisyphus may find joy in his struggle and descent, but Tecumseh’s mountain is washing into the sea.

But I like the losing side. Something in my DNA remembers enough to weep when I see places I know by name disappear forever, subsumed in the grey, rectangular world of progress and civilization.

“But Wayne,” you might say, “can’t you see that by <insert metric here> things are objectively better under this victorious regime?” Yes, yes I can. I can’t deny it (though I’m not so sure anyone is as right as they are confident). But I’m not a rational person; I’ve never even met such a person. I don’t wanna get too off track here, but I’m not even sure that the God in whose image I’m made is quite what we’d call rational. He feels things, just like us, after all. He once even wanted to destroy a whole city of evildoers because the sound of so many people suffering there got Him all worked up—a feeling many humans have felt and even acted upon—and it was Abraham who “rationalized” Him out of it.12

I’m not really into this world of progress, though I lack grounds to condemn it. We’re progressing fast, that’s for sure. But who said that the goal of humanity is to live to be 100 without breaking a sweat or lifting a finger? Since when is progress defined as colonizing the moon and Mars and beyond?

“Human beings have set off at astronomically high speeds toward nowhere.” — Jacques Ellul

13And hey, maybe our space-race gods Bezos and Musk et al will save us and the planet. But I’m not really sold on human saviors, and I don’t think we have to leave earth to save it; it will be redeemed too.

“creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the freedom and glory of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time.” — Rom 8:21-22, NIV

I’m interested in living, really living. I’m interested in earth: the practically infinite world of learning, loving, and sweating. If I can do it till I’m 100 then I’ll do it gladly, but how long I’m here for isn’t really a question that concerns me. I’m interested in living a life that postpones an end that geologists assure me is inevitable,14 and proclaiming an alternative.

It’s not that the victorious culture, or lack thereof, is worse than what we have, or that progress is bad. It’s not that things will be worse off in the future if we don’t hold on to archaic values—though we can never rule it out. It's not even that I want to turn back the clock to some mythical golden age (“it is not from wisdom” that one seeks the former days, says Ecclesiastes15). It’s that there’s some good being lost. There’s good being forgotten. Said a gardener, “There’s some good in this world, and it’s worth fighting for.” That’s why I pick the losing side: to be a force of preservation of the good. It’s not whitewashing to say that some good was lost when the Tecumsehs and the Quanahs of the 1800s were laid to rest.16

Who can sell the air, and who can sell the sea?

Who has the right to sell the land put here for you and me?

Tecumseh get your rifle, Tecumseh get your gun,

For on the field tomorrow morn, you’ll meet with Harrison.

…Tecumseh, he was shot down upon the field in Thames

Around him lay the wounded and dying Shawnee Braves.

Tecumseh get your rifle, Tecumseh get your gun,

For on the field tomorrow morn, you’ll meet with Harrison.

Remember all you people, the man so true and brave,

His family and his freedom, he fought so hard to save.

Tecumseh get your rifle, Tecumseh get your gun,

For on the field tomorrow morn, you’ll meet with Harrison.

— The Tillers, “Tecumseh on the Battlefield”

Tecumseh is deserving of the label American archetype along with others, such as legendary long hunter Daniel Boone or the lesser-known slave and warrior Holt Collier, all of whom provide incredible examples of both conquerors and victims, exploiters and nurturers. America really isn’t special in producing these types, but maybe we’re special in that they make up our DNA and we’re proud of it.

So yeah, I side with Tecumseh. I side with my fellow sticks in the mud. And I’ll lose with them—“thus I want to die myself that you, my friends, may love the earth more for my sake.”17 But there will be more Tecumsehs, even if they fight for values I don’t understand on cultural battlegrounds I can’t foresee. There will be some truth in what they say, and they will be mostly ignored, and they will lose. But humanity has always needed their voice and it always will.

In the last days of Tecumseh,

There, in the end,

There were rumors of invasion,

Even talk of spacemen.

But he couldn’t believe all that he knew would fade;

In the ground below the airplanes, Tecumseh were laid.

— Grant-Lee Buffalo, “Last Days of Tecumseh”

Opening quote from Thus Spoke Zarathustra: First Part by Friedrich Nietzsche, translated by Walter Kaufmann.

If you’re interested in learning more about Tecumseh, I would recommend these resources: Tecumseh and the Prophet: The Shawnee Brothers Who Defied a Nation by Peter Cozzens, and episodes 88-93 of the wonderful Bear Grease Podcast hosted by Clay Newcomb.

Don’t get me twisted: I love Texas, and Texans. I’m not interested in making qualitative judgements about who was in the right and wrong, and many of the Plains Indians were so violent that the attempts of pioneers and other Native Americans to annihilate them sometimes seem reasonable in hindsight. Texans were moving west, and they were the only people tough enough to do it in those grisly decades of North American history.

For a beautiful telling of the rise and fall of the Comanches and their final chief, Quanah Parker, I recommend Empire of the Summer Moon by S.C. Gwynne.

I don’t mean to whitewash here; some of the plains tribes, especially the Comanches and Kiowas, were incredibly violent peoples who lived by the same sword they died by. Qualitative judgement on their lifestyle isn’t really relevant to my point.

Quote from The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture, by Wendell Berry. To say that the Indians merely “accepted” this dependence, as if the only factor were their own free will, would be false, but the statement as a parable is generally accurate and holds for other people groups as well. I would say that it holds for you and I.

Fun fact: Tecumseh was a teenager when he fought in the Battle of Blue Licks in 1782, where Daniel Boone’s son Israel was killed. It is possible, though unlikely, that Tecumseh even fired the fatal shot. Small world. Also, if you’re interested in learning more about Daniel Boone then I highly recommend Boone by Robert Morgan and episodes 14-19 of the Bear Grease Podcast hosted by Clay Newcomb.

If you’re interested in leaning more about this unfortunately overlooked character in American history, I highly recommend Holt Collier: His Life, His Roosevelt Hunts, and the Origin of the Teddy Bear by Minor Ferris Buchanan and episodes 68-72 of the Bear Grease Podcast hosted by Clay Newcomb.

Quote from The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture, by Wendell Berry.

I say “their” though on my best days I’ve been accused of belonging to these groups. Alas, I’m afraid I do not deserve the honor.

I’m thinking here not only of labels like “redneck” or “hillbilly” but also of things like confederate flags, truck culture, country and folk music, etc.

Gen 18:20-33.

Quote from Presence in the Modern World by Jacques Ellul, translated by Lisa Richmond.

It’s ironic that the people who push the hardest for escaping the planet as a means of escaping finiteness conveniently ignore the reality that the entire universe awaits the same end. Choose nihilism if you want; I choose faith.

Ecc 7:10.

Just as the author of Ecclesiastes reminds us that there is no true memory of the past, and that the progress of tomorrow will not change a mote about the human condition, he provides a great comfort when we think about good things lost to us: “That which is, already has been; that which is to be, already has been; and God seeks what has been driven away” (Ecc 3:15, ESV). We may forget the good in our past, but God will not.

Here, I pervert Nietzsche’s passage to mean the opposite of what I think he meant. But he can't do anything about it because he’s dead.

Great essay!